Knowledge Exchange Recap: Housing Mobility Strategies

Each month we’re reporting out on our Knowledge Exchanges, held as part of our Visiting Fellowship in Urban Poverty with Loyola University of Chicago’s Center on Urban Research and Learning (CURL).

In May our discussion was lead by Barbara A. Samuels, the Managing Attorney for ACLU of Maryland’s Fair Housing Project. The recap below of the session’s conversation is provided courtesy of our Visiting Fellow.

Barbara Samuels is the managing attorney for the ACLU’s fair housing project, and oversees the implementation of the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program. The program was launched in 2003 as the result of the Thompson v. HUD lawsuit. Peter Rosenblatt is working with Stefanie DeLuca at Johns Hopkins University to evaluate the program. Since its launch, 2500 families have moved to opportunity areas. The program will continue to expand by 400 vouchers per year to a total of 4,400 vouchers by 2018.

So far, the program has successfully facilitated long-term moves to opportunity areas. Eighty-four percent of participants are living in neighborhoods with poverty rates of less than 20% two or more years after their initial move, including participants who moved when the program was launched 10 years ago. The average participant is living in a neighborhood with a poverty rate 9.8% and children are attending schools with lower poverty rates, higher test scores, and more qualified teachers.

There are several key elements that differentiate the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program from other voucher programs. First, it is overseen by the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership (rather than the Baltimore Housing Authority). So vouchers are administered regionally, which eliminates the need for portability procedures. Second, the voucher administration and the housing counseling are administered by the same agency, so there is better coordination between these aspects of the program. Finally, the program was granted a HUD exception which allows voucher payments of up to 130% of FMR, which facilitates moves to middle and higher income neighborhoods.

“Eighty-five percent of recent movers surveyed in 2008 said that their quality of life improved following their move to a new neighborhood…

As examples of such quality of life improvements, 86 percent said their new neighborhood offers a better environment for children and 62 percent said it offers more green space and fresh air.

Nearly 80 percent said they feel safer, more peaceful, and less stressed. 40 percent of participants reported feeling healthier.”

-Lora Engdahl, 2009, “New Homes, New Neighborhoods, New Schools: A Progress Report on the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program.” Poverty and Race Research Action Council. Click here to download the report.

Discussion Summary

How does the Baltimore Mobility Program work? Who is eligible, how to do participants become involved, how are target neighborhoods selected, and how intensive are the services?

Program eligibility was initially restricted to residents of public housing, residents who were displaced from public housing, and the public housing waiting list. Today, it is open to anyone who is eligible and living in a Baltimore city neighborhood that is more than 75% African American. However, there is a preference for public housing residents, and as of July 1, 2014 there will be a preference for families with children under the age of eight living in a neighborhood with a poverty rate of 30% of above. There is an overwhelming demand for the program. The program can accept 150 applicants per month, but receives between 600 and 800 applications on a monthly basis.

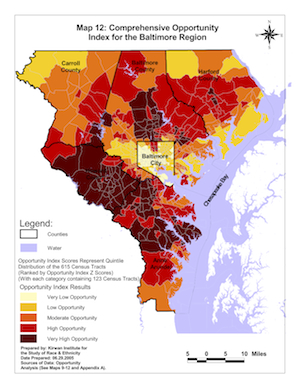

In order to receive a voucher, residents are counseled to save $500 towards their security deposit and the program pays the balance. They also attend an orientation and workshops, and in most cases, make efforts to repair their credit. In order to encourage moves that are less disruptive for school age children, the security deposit requirement decreases to $200 in the summer months, and the Mobility Program pays the difference with funds provided by the Abell Foundation. On average, this pre-move counseling and preparation process takes 12-14 months. Vouchers must be used in opportunity areas that have poverty rates of less than 10%, have less than 5% assisted housing, and are less than 30% African American. Residents must also commit to living in an opportunity area for two years, although they can move within the opportunity area if there is a problem with their unit or landlord.

Housing counseling services include housing search assistance (including tours of different neighborhoods), orientation to the new neighborhood, and post-move support, including landlord/tenant mediation. Initially, the pre-move counseling was conducted on an individual basis, but the program now utilizes a workshop format which is more cost effective and popular among participants. The program does not provide intensive case management, and participants receive referrals for specialized services such as GED and job training. Most participants require minimal services once they’ve settled into a new neighborhood, but services are available for up to two years post placement. It is not uncommon for participants to eventually move from their first apartment, so in 2008, the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program instituted second move housing counseling to ensure that participants remain in opportunity areas.

The Baltimore Housing Mobility Program is unique because it primarily serves families with children, which translates into a need for larger apartments and homes. In contrast, most municipally-run voucher programs are dis-incentivized from serving families because larger units are more expensive and can be harder to find.

What are some of the implementation challenges?

The Baltimore area has very limited public transportation, and new participants are very concerned about navigating an unfamiliar neighborhood without a car. This concern can be a significant barrier to participation. The Baltimore Housing Mobility Program provides funding for drivers education classes (a requirement to get a license in the state of MD) and has partnered with Vehicles for Change, a program that repairs donated cars and sells them inexpesively to low income working families.

The Baltimore Mobility Program was granted an FMR exception so participants can rent units up to 130% of the FMR, which has helped secure units in opportunity areas with higher rents. Without an exception, the FMR calculation is a major obstacle for many mobility programs. In Dallas, HUD was sued by the Inclusive Communities Project, and as a result of the lawsuit, the Dallas area FMR’s were temporarily recalculated based on zip code. It was determined that HUD was overpaying in low income neighborhoods, and underpaying in opportunity areas. The Dallas example demonstrates that a federal recalculation of FMR’s could allow for more vouchers in opportunity areas without significantly increasing the cost of rental assistance. However, there has been a great deal of opposition to reducing the FMR’s in low income areas.

Finally, some landlords continue to discriminate against voucher holders. Maryland could benefit from an ordinance that bars housing discrimination based upon source of income.

The MTO evaluation showed little improvement in academic performance and there is some data which suggests that teenagers may actually do worse in new schools. What is the relationship between attending a higher performing school and increased academic performance?

When you look at the MTO data in aggregate, there is no significant academic improvement, but when you disaggregate the data by city, there are improvements in Baltimore and Chicago. However, these improvements seem to be largely due to decreased levels of community violence for experimental group movers. There is growing evidence that violence and trauma can have long term effects on academic outcomes. This is a key reason that the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program is now prioritizing families with young children. Stefanie DeLuca and Peter Rosenblatt are currently comparing the educational outcomes of Baltimore Housing Mobility Program participants with a comparison group.

Back To Blog