Knowledge Exchange Recap: Chicago’s Homelessness and Supportive Housing System

Each month we’re reporting out on our Knowledge Exchanges, held as part of our Visiting Fellowship in Urban Poverty with Loyola University of Chicago’s Center on Urban Research and Learning (CURL).

In September our discussion on Chicago’s homelessness and supportive housing system was lead by Betsy Benito, Director at the Corporation for Supportive Housing and Nancy Radner, Chief Operating Officer at the Primo Center for Women and Children. The recap below of the session’s conversation is provided courtesy of our Visiting Fellow.

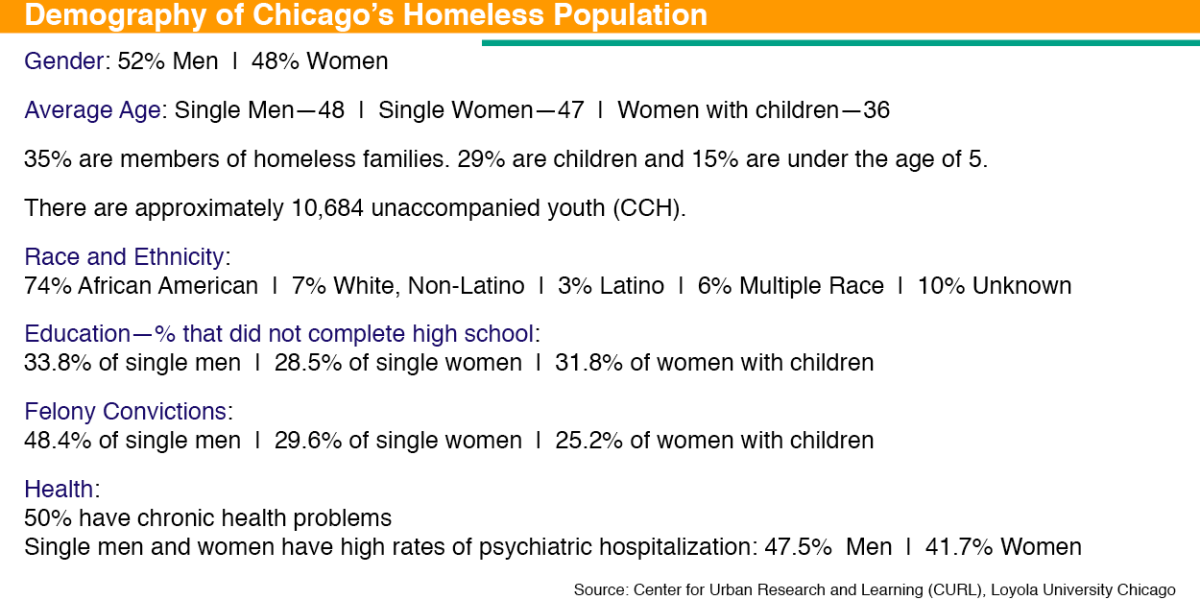

Homelessness has always been an issue, but was exacerbated in the 1980’s, as social welfare programs were dismantled, residential mental health institutions were closed, and the nation experienced an economic downturn. Currently, we estimate the number of people experiencing homelessness by using a HUD mandated biannual point in time count. In late January, volunteers, case managers, outreach workers, and homeless individuals canvass the streets and survey homeless shelters to determine the size and demographic characteristics of the homeless population. The 2011 point in time count found that, on any given night in the City of Chicago, there are 6546 homeless people. Twenty-five percent were found on the streets, while the remaining 75% were in a shelter. Thirty-five percent were part of a larger homeless family.

The point in time count does not include individuals and families who are “doubled up,” meaning that they do not have a home and are temporarily staying with friends and family. The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless estimates that 93,779 people are homeless over the course of the year if you include the doubled up population. CPS estimates that in the 2011-2012 school year, 16,600 students were doubled up or utilizing shelters.

Job loss, physical and mental health issues, eviction, and substance use are common causes of homelessness. In addition, since many people are doubled up prior to entering the homeless system, interpersonal conflict and the withdrawal of support from friends and family members are also reported as immediate causes of homelessness. Ultimately, homelessness is a matter of poverty—very poor people are economically vulnerable, and interpersonal problems, health issues, and job loss are more likely to end in homelessness.

In 2000, the National Alliance to End Homelessness developed a strategy to fundamentally change the homeless service delivery system: proposing a goal of ending homeless in ten years using a “housing first” approach. Up to that point, emergency shelters and temporary housing combined with some services (rather than permanent housing) were the primary vehicles for addressing homelessness. However, this had been an ineffective model. It became clear that being without a home is an extremely destabilizing condition, and it was difficult for people to address the multiple causes of homelessness (physical and mental health issues, job loss, etc.) without a roof over their head. Policy oriented researchers and service providers began to experiment with a “Housing First” model, which provided immediate access to permanent housing, paired with voluntary supportive services. The model proved to be more effective and less expensive, as housing first participants were less likely to use other public services, and had lower rates of hospitalization, emergency room visits, and arrests.

Municipalities began to implement 10 Year Plans that were tailored to the unique needs and strengths of their local communities. In 2003, Chicago began it’s 10 Year Plan, which brought together homeless service providers, foundations, and representatives from local, state and federal government to reconfigure the homeless service system. Chicago’s 10 Year Plan has been characterized by the production of permanent supportive housing, the development of interim housing, and a de-emphasized role of emergency shelters. Interim housing was designed to replace emergency shelter as the first point of contact within the system. Interim housing provides immediate access to housing, more intensive services, and is focused on finding a permanent housing solution. A second characteristic of Chicago’s 10 Year Plan is a focus on harm reduction, a service delivery approach that does not require strict adherence to a set of predetermined program rules, such as abstinence from drugs or required medication. Instead, clinical staff work collaboratively with the each person to determine a course of action that will lead to greater health and stability. In the case of serious substance use issues, the end goal may be sobriety, but individuals can take progressive steps towards meeting that goal.

Discussion Summary

Chicago just completed a 10 Year Plan, and has created the Plan to End Homelessness 2.0. Was it successful? What is left to do?

The 10 Year Plan created a significant number of permanent supportive housing units, and the harm reduction approach is being adopted by a growing number of homeless service providers. Evaluation of the 10 Year Plan found that the new housing model “interim housing” was significantly more successful in its ability to move individuals to permanent housing than emergency shelters. In Chicago, there are 8,000 permanent supportive housing units—two thirds of the units are project based supportive housing (such as Deborah’s Place or Mercy Lakefront) and the remaining units are scattered site housing. In addition, many emergency housing programs converted to interim housing. Currently, homeless individuals and families rely on word of mouth when applying to supportive housing programs. The 2.0 Plan prioritizes the development of a centralized referral system and increasing housing and service programs for homeless youth.

Despite the growth in supportive housing production, there is still an unmet need—it is estimated that Chicago requires 2000-3000 more units to house the chronically homeless in the City of Chicago. The average time on the waiting list for permanent supportive housing is nine months. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has a dedicated funding stream for supportive housing (the HUD McKinney Vento program), but the funding for this program has been cut. Furthermore, the production of supportive housing was a priority for the Daley administration, but the Emanuel administration has different priorities. Consequently, there has been a lag in supportive housing production and an inability to add new units to the system in recent years.

The new Plan to End Homelessness has placed an emphasis on creating units for homeless families, which make up 1/3 of the homeless population. The homeless service system was originally designed primarily for single individuals, and it was common to separate families in order to obtain housing. Domestic violence is often a cause of family homelessness, yet there is little overlap between the domestic violence service delivery system and the homeless service system. This is an example of a fundamental problem—the lack of coordination between various social service fields, such as housing, health care, substance use and domestic violence.

Back To Blog